www.tracker.org.au |

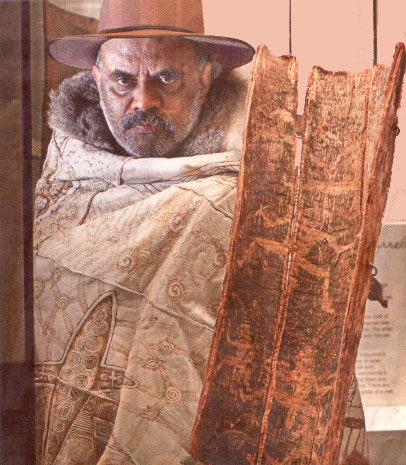

Barks Bite the British Museumby Gary Foley Tracker Magazine 12th March 2013

This month I would like to tell the story of why three of the rarest items of Aboriginal art in the world today sit in a cupboard in the British Museum in London, never to be returned to their rightful custodians the Dja Dja Wurrung people in Victoria. It is also a tale of a brief, heroic battle in 2004 by the Dja Dja Wurrung to seize and reclaim those items; a battle that was lost because of the duplicity of officials at Museum Victoria. It also happens to be the story of how on a question of principle, I resigned and walked away from the best job I have ever had in my life.

In 2002 I was employed by Melbourne Museum (now known as Museum Victoria) as Senior Indigenous Curator for South-Eastern Australia. It was during a brief period of enlightened policies on the part of the Museum that saw it make a token attempt to give Aboriginal people a voice in the manner of their representation in such an institution. For a brief period in the early 2000s Museum Victoria was a world leader in developing better relations with Aboriginal peoples. After all, this same Museum had a shameful past in its treatment of Aboriginal people, especially in the manner of its representation of Aboriginal people in its exhibitions. Melbourne Museum had been one of the institutions in Australia that had notoriously displayed in a glass case the skeleton of Tasmanian woman Truganini, despite her desperate pleas before she died for this not to happen to her.

But by the early 2000s it seemed that the Museum Victoria was prepared to change its ways and was allowing Aboriginal peoples a greater say in its policies. For this reason I decided to apply for a job there and for the first twelve months I thoroughly enjoyed working with a team of Aboriginal people who seemed to be valued by the Museum management. My life experience up to that point should have warned me that such an idyllic situation could not last. As indeed it didn't.

The crunch began one day in 2003 when a curator from a different section in the Museum came to me and told me that she had just returned from England and whilst there she had spent some time researching in the British Museum. She told me that she had discovered in a cupboard three items that had been collected in Victoria and sent to England in the 1850s, during the period that the Aboriginal nations in Victoria were being invaded and dispossessed. That was not unusual, but what made these three items incredible were that they were items of bark art. As such they were the only surviving examples on the planet of Victorian Aboriginal bark art. Unlike bark art of northern Australian, these Victorian examples had etchings burnt into them. Thus, these items found in the British Museum were a priceless part of not only Dja Dja Wurrung heritage, but also part of the national cultural heritage of Australia.

As soon as I found out about these barks in the British Museum I contacted an old friend and fellow agitator, Mr Gary Murray, who also happened to be an Elder of the Dja Dja Wurrung, to whom these barks belonged. Murray and I had been involved in numerous political battles together over three decades previously, and immediately we began to plot a way in which we might be able to get these three barks returned to their rightful owners. Whilst the thought had crossed my mind that I might have technically be acting inappropriately given my position at the Museum, I had always believed that my allegiances would always be with Aboriginal people regardless of whoever my employers at any given time might be.

The first problem for the Dja Dja Wurrung was that the barks were in the British Museum. This was (and is) an institution that is notorious for its absolute refusal to repatriate anything from its collections, most of which had been accumulated during the era of looting and plunder known as the British Empire. But the primary reason why the British Museum remains to this day so recalcitrant on the issue of repatriation is because of what are known as the “Elgin Marbles”. These were an collection of classical Greek marble sculptures that originally were part of the Parthenon in Athens. In one of the most notorious cases of cultural theft and vandalism in history, the British Ambassador Lord Elgin cut up these sculptures and shipped them to England, where in 1816 they were placed on display in the British Museum.

Almost ever since then Greeks have been calling for the return of the Parthenon Marbles and the British Museum not only refuses point blank to return them, but also believes that repatriation of any looted materials to anywhere else might create a precedent that would allow for possible return of the Elgin Marbles. So Murray and I were aware from the start what we were up against.

I knew at the time that the 150th Anniversary of the Melbourne Museum was imminent so I put a proposal to the Director that it might be a good idea for the anniversary celebration for Melbourne to see if the British Museum might be prepared to lend these three barks to our Museum so that we might exhibit them as part of Melbourne Museum's 150th. When I did this I was aware of two things.

I knew that the recently appointed Melbourne Museum Director Patrick Greene had extensive contacts among English museums and would likely be able to negotiate such a deal with the British Museum. I was also aware of a unique provision under the then National Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Act whereby only Aboriginal people in Victoria were able to make an “Emergency Declaration” on important cultural objects and in effect seize such items. Gary Murray and I decided that if we could actually get these three barks into the premises of the Melbourne Museum, then Murray would be in a position to make an emergency declaration on them and they would not be allowed to be moved until proper ownership could be established. It was a great plan. Not only had we conceived a way to seize the barks, but also to highlight the problem of stolen Aboriginal cultural objects and human remains in museums worldwide.

The first part of the plan worked perfectly and the three barks duly arrived at the Melbourne Museum. Gary Murray and the Dja Dja Wurrung caught the British Museum by surprise when they then secured an emergency declaration over the barks. Reaction from Britain was both swift and predictable. The London Times in July 2004 reported that Tristram Besterman, director of the Manchester Museum, was particularly shocked and that “More can be achieved through a “proper spirit of discussion”, he said, rather than by “extortion and blackmail”. The Times reported that Gary Murray was unrepentant. “They belong in Australia. If we had your Crown Jewels, you'd be knocking our doors down,” he said.

For a brief period it seemed the Dja Dja Wurrung had outmanoeuvred the museums, but they had not counted on the determination of the British Museum to ensure that no precedent was created that might endanger their retention of the Elgin Marbles. The British Museum immediately threatened the Melbourne Museum by pointing out that Melbourne would be in breach of contract with the British Museum if the barks were not returned. Rather than doing their own dirty work, the British Museum insisted that Melbourne Museum take legal action against the Dja Dja Wurrung to have the emergency declaration lifted.

The Melbourne Museum, terrified that this episode would threaten their ability to borrow exhibitions from other museums worldwide, seemed more than happy to comply with the British Museum's demands despite recognition in Victorian law of the vital need to protect Aboriginal ownership of stolen cultural property. The Chairman of the Board of the Melbourne Museum, Harold Mitchell, who was described at the time as one of the richest men in Australia, flew off to London to have a meeting with his British Museum counterpart.

Under the Federal Aboriginal Cultural Heritage legislation the emergency declaration could be renewed and extended indefinitely, and duly authorised Aboriginal inspector Rodney Carter had exercised this provision several times on the barks, and Melbourne Museum lawyers, desperately looking for a point on which to challenge the legislation, went to court to challenge Carter's ability to do this. The instant that the Museum decided to take the Dja Dja Wurrung to court, I knew that my position had become untenable. I went to the office of Museum Director Patrick Greene and advised him that on principle I could not work for an organisation that took court action against Aboriginal people defending their rights. I resigned on the spot and thus walked away from the best job I had ever had.

Meanwhile, as the court challenge continued there was extensive, world-wide media coverage and strong support for the Dja Dja Wurrung. As coverage dried up, and now that I was free to take a more public position of support for the Dja Dja Wurrung, I helped out in developing battle strategy with Gary Murray.

At one point it occurred to me that there was a reservoir of goodwill and support that we were not tapping into.

I said to Gary Murray, "Hey, what is Melbourne?"

Murray said, "What?"

I reminded him that Melbourne is in fact the biggest Greek city in the world outside of Greece.

I then said to Murray, "Who in the world hates the British Museum as much as we do?"

Murray replied, "Greeks!"

I said, "Indeed!"

So we made a telephone call to the editor of the local Greek newspaper, Neos Kosmos, and made an appointment to see him the next day. It did not take more than one minute of explanation as to why we were there for the Greek newspaper people to instantly understand why we had come to see them. Especially when they realised that the main reason the British Museum was absolutely refusing to return the barks was because they didn't want a precedent established that might strengthen Greek demands for the Parthenon Marbles. The end result of that excellent meeting was a front page article in Neos Kosmos strongly in support of the Dja Dja Wurrung.

The sad part of this story is that despite extensive local and overseas support for the Dja Dja Wurrung to have the barks returned, the Melbourne Museum's resources and influence prevailed in the court case. The barks were duly returned to the dusty British Museum cupboard they had occupied for the previous 140 years, much to the relief of museum officials. The Dja Dja Wurrung and the people of Australia have again lost three important objects of cultural heritage, and it was all due to two things.

The first was the almost rabid determination of the British Museum to keep secure their retention of the vandalised and looted objects belonging to the Greek people. The second reason was a spineless and cowardly Melbourne Museum administration meekly kowtowing to threats from the British museum establishment. Needless to say, the good reputation in regard to relations with Aboriginal peoples that Melbourne Museum had up till then been developing came crashing to a heap. Melbourne Museum demolished the goodwill of the Aboriginal community in one fell swoop, and it has never recovered to this day.

To Murray and I it was but one of many battles we have fought together over the past 30 years, many of which we won, some of which we lost. I may have walked away from a great job, but I retained my integrity which was much more important to me than money and prestige. But one good thing came out of it all. We now have a lot more Greek friends.

Gary Foley

|