Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Important People in the Political Struggle for Aboriginal Rights

| ||||

1936 - 2000 | ||||

|

||||

|

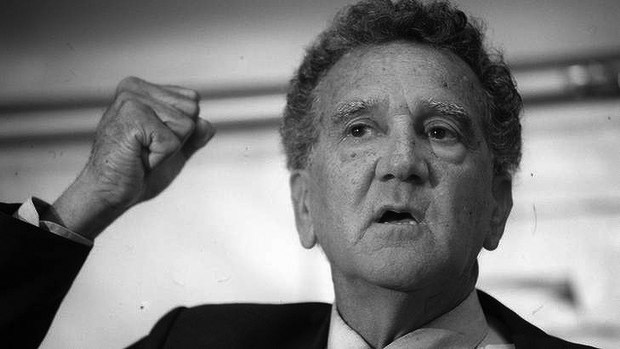

CHARLES PERKINS

1936 - 2000

Obituary

19 October 2000 - Aboriginal leader who campaigned for civil rights reform and was the first of his people to become head of a government department.

The first Aboriginal Australian to become head of a federal government department - the Department of Aboriginal Affairs - Charles Perkins exerted an enormous influence on Australian national life for more than 40 years. Throughout that time he

was the most outspoken activist for Aboriginal rights. A man given to a certain vehemence in propounding his views, as recently as last May he had described Australia's

Prime Minister, John Howard, as a "racist" and a "dog" for what he regarded as his tardiness in embracing reconciliation with black Australia. Perkins demanded a full government

apology for past wrongs to the Aborigines. "Without an apology there can be no real reconciliation, and the conscience of the nation will never rest in peace."

Charles Perkins was not only the first Aboriginal Australian to become head of a government department; he was, in 1965, also the first Aboriginal university graduate. Three years

ago he was declared a "living treasure" by the National Trust.

Charles Nelson Perkins was born in 1936 on a table in Alice Springs telegraph station, the son of Martin Connolly and Hetti Perkins.

Though his grandmother was a full-blood of the Arunta tribe, his grandfather on his mother's side was a white man, Harry Perkins. Charles Perkins retained his mother's name.

Perkins always claimed to be a member of the so-called "Stolen Generation" of Aborigines who were forcibly taken from their black families to be raised by white families or in

white institutions. He was, in fact, placed in a school by his mother who sought help from a government official after her husband had deserted her following the birth of her 11th child.

At the age of ten Perkins was sent to St Francis Anglican House in Adelaide to have, in his words, "the colour washed out of me".

He was intelligent and argumentative, but it was initially sport, not education, which rescued him from the life of poverty endured by his family. At 15, he

became an apprentice fitter and turner at British Tube Mills, but his first love was soccer. This talent had emerged at St Francis and he later progressed to the

senior ranks in the ethnic clubs in Australia.

He had early first-hand experience of racism. As he relates in the biography Charles Perkins, by Peter Read, he was once rejected by every single

woman at a Port Adelaide Town Hall dance. He had summoned the courage to walk across the room and asked each individually, only to be told: "We don't dance with blacks."

The experience, he said, scarred his mind and undermined his confidence and self-respect.

Meanwhile, his skill on the soccer field had caught the eye of a talent scout from Everton Football Club who paid half his fare to England to try him out.

He arrived midway through the 1957 season but soon realised he should have been much fitter. He did not make the Everton team but was eventually

offered a contract with Manchester United.

But by now he felt homesick. He declined the Manchester United offer and returned home to a job as captain-coach of an Adelaide team.

He arrived back in Adelaide in June 1959, but his experience of having been accepted in the more tolerant racial climate in England had left its mark, and he began

to consider a life devoted to the Aboriginal cause.

In January 1961 he met Eileen Munchenberg. Her family, descendants of German Lutherans, welcomed him and the couple married in September that year.

Settled in married life, Perkins began studying anthropology, psychology and political science at Sydney University and became president of the Students' Action for Aborigines.

The year before his graduation, Perkins achieved national publicity through a series of civil rights protests which were conducted in the manner of those of Martin Luther King.

His "Freedom Ride" bus tour went to areas of Australia where an Aboriginal could not try on clothes in a store, sit down in a restaurant, get a haircut, go to secondary school or work

in a shop. At every stage along its route his campaign confronted segregation and discrimination, winning several civil rights victories, notable among them the abolition of a ban on

Aboriginal children using the public baths in the town of Bourke.

Perkins's memories of this campaigning journey as retailed in Read's biography were of “the flying gravel, the tomatoes and rotten eggs, the punches, the spit, and the shouted threats:

'Let's string 'em up.' 'Come down here, mate, we want to have a yarn with you.' ' Get the coons out. Get the coons out'.

He was soon active in the fields of Aboriginal housing, health and education, and he campaigned hard to obtain better conditions of employment for Aborigines.

In 1967 he joined the federal public service as a research officer and went on to serve for 21 years, rising to become head of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs,

before his outspoken political criticism drew him into open conflict with the Labour Minister Gerry Hand, who in 1988 sacked him over allegations of maladministration.

Before that, Perkins had clashed repeatedly with white leaders. In 1982 he urged the Queen to boycott the Commonwealth Games in Brisbane, saying Queensland was racist.

The following year he drew on himself the ire of the right-wing Premier of Queensland, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, when he suggested that English names for towns and geographical

features be abolished in favour of the traditional Aboriginal ones.

Bjelke-Petersen riposted by suggesting that Perkins change his name to "Mr Witchetty Grub".

Perkins's most provocative comments came earlier this year when he urged British tourists not to come to the Sydney Olympics. He painted a lurid vision in

which buildings and cars would be burnt by protesters. “It's burn, baby, burn from now on. Anything can happen.” Naturally, his comments provoked national outrage.

Yet, as Aden Ridgeway, the only Aboriginal in Australia's federal parliament, said of Perkins: "Love him or hate him, no one could help but admire the man for his passion, his

commitment and his lifelong work in the struggle to get better opportunities for his people."

Charles Perkins, Aboriginal campaigner, was born on June 16, 1936. He died of renal failure yesterday aged 64.

Cleansing smoke in tribute to Perkins

Age, The (Melbourne, Australia) - Saturday, October 28, 2000 Wind lifted smoke from the smouldering gum leaves, twisting and turning as if deliberately daubing each of the 80 mourners huddled in front of Trinity College chapel. By the time they filed into yesterday's memorial service for Charles Perkins, their hair and clothes were fragrant with it. "The smoke is to cleanse everyone coming in. Make sure they come in of good heart and are clean of spirit in paying their respects and celebrating his life," filmmaker Richard Frankland explained. On Wednesday, Charles Perkins was remembered at a state funeral in Sydney. Yesterday's memorial service allowed Melburnians to pay tribute to perhaps Australia's most influential Aboriginal activist, a man who journalist John Pilger recently said was in many ways Australia's Nelson Mandela. Among the mourners were several local Wurundjeri elders, local artists, activists and academics. Gary Foley delivered a eulogy, shifting nervously from foot to foot, often choked with emotion. Mr Foley spoke of the inspiration the freedom rides, led by Dr Perkins in 1965, had given him as a skinny, impressionable 15-year-old boy. "I was profoundly affected by this man and inspired to do most of what I've done in my life," he said. He said Dr Perkins had helped him when he first fled to Sydney from the "Ku Klux Klan" town he grew up in on the northern New South Wales coast. He talked of how he would fight with Dr Perkins and described how he learnt from him that it was possible to stand up and be counted. "You can't have a long-term relationship with a man like that and not have spats," he said. "This man had a profound effect on an entire generation. Virtually everybody who came along after him had been in some way influenced, inspired, motivated in some way by what he did." Outside the church, Richard Frankland said that Dr Perkins was one of Australia's greatest patriots who had the courage to see what was wrong with Australia and the tenacity to stand up and say "let's fix it". Mr Frankland said that when he was born he wasn't a citizen. But due to the work of people like Dr Perkins he could now vote.

| ||||