Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Important People in the Political Struggle for Aboriginal Rights

| ||||

1928 - 2010 | ||||

|

||||

|

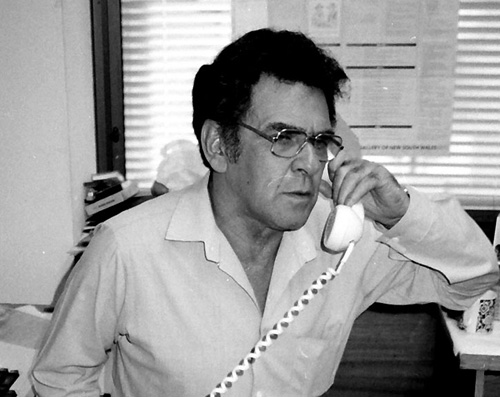

Charles 'Chicka' Dixon: Docker, Trade Unionist, Aboriginal rights activist. Thursday, 8 April 2010 Waterside worker and long-time Aboriginal activist Charles "Chicka" Dixon died in Sydney on March 20, aged 81 - struck down by asbestosis he contracted while working on the wharves. Chicka Dixon - Aboriginal of the Year, Tent Embassy activist, builders’ labourer, wharfie, university lecturer, recovered alcoholic and former chair of the Aboriginal Arts Board, a man who represented his people around the world, studied with the Canadian Native Americans, did a bit of jail, was mates with prime ministers Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke and addressed 10,000 Chinese people in the Great Hall of the People — has died. Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) national secretary Paddy Crumlin paid tribute to Chicka, a political and labour warrior. "The MUA adds their sympathies and condolences to the many voices in our national and the international labour movement on Chicka's passing", he said. "A man of character, substance and unwavering courage, he reflected the finer traits Australians aspire to and seek after for a society that is decent, inclusive and fair to all." "Chicka was a worker, leader and activist who was determined to turn around racism and elitism and gain proper recognition for the extraordinary culture and character of his people and the great injustice done to them. His asbestosis-related death brings into even clearer focus this great injustice to working men and women in this country and the long campaign led by the MUA in many ways to find remedy and restitution. Our membership officials and staff in particular farewell one of our own. Vale comrade." In an interview with the union's journal in 2001, White plague strikes Black elder, Chicka recalled his exposure to asbestos on the Sydney wharves in the 1960s. "It would fly all over the place", he said. "Heaps of it. My gang, we'd sit on the bags and eat our lunch. Bags and bags of asbestos. No one knew. We usen't to take any notice. Forty years down the road, in 1997, I collapsed." "When they examined me, they said ‘you've got dusty lungs’. All those years, I'd never been sick in my life. I've been 12 times in hospital in the last two years. Seven days to pump my lungs out." Dixon left the Wallaga mission on the NSW south coast for the city in 1945. By 1946, Chicka told the Maritime Workers’ Journal, ``I was sneaking off to meetings of the Aboriginal Progressive Association at the Ironworkers’ Hall [the FIA at the time was controlled by the Communist Party of Australia]. `Oh Chicka, don’t go down there, they’ll call you Red’, my mother said. `Well, I said, they’ve been calling me black for years'.’‘ After a stint as builders’ labourer, he got a job as a wharfie and was a militant with the CPA-led Waterside Workers Federation. ``That’s where I learned the politics. The Communist Party Moscow liners were masters of organising. And I learned a lot about other people’s struggles... I was in a bit of a shell before that. I thought we were the only people in the world discriminated against. Then I started to hear about Greek political prisoners (we walked off on that issue), the Vietnam War (repeatedly walked off on that) and South Africa (walked off on that, too)... That was my political education ... They taught me how to organise. We’d be talking politics all the time. It was second nature’‘. Harry Black, from MUA Veterans, worked alongside Chicka at Darling Harbour. "Chicka was very active as an Aboriginal activist and as a unionist", he said. "He played a very significant role on wharves continually putting forward the Aboriginal cause and working closely with the union to bring about support. Under his influence, quite a few Aborigines came to the waterfront and became members of the waterfront.Chicka was dedicated to the struggle for betterment of his people." Through Chicka's and other Indigensous activists' direct involvement with the left and labour movement, the Indigenous people’s rights movement could call on the power of working-class action in many situations. An example was provided by Chicka Dixon: I was in bed and three young Aborigines knocked on the door about nine o’clock at night. They told me that a very dignified hotel down in George Street [in Sydney] wouldn’t serve Aborigines. I decided to go down and find out. I took the blackest fella with me, walked in, and asked for a schooner of beer for my friend and schooner of lemonade for myself. The bartender said: `I’m sorry... We won’t serve Aborigines.’ `Well that’s quite all right, [Chicka replied], tomorrow evening I’ll have 300 waterside workers up outside your joint here. Nobody is going to get in because we are going to blacklist this hotel. Then I’ll go to the Trades and Labour Council and the Liquor Trades Union to pull the barmaids out.’ Well, he did complete [about] face. It’s a remarkable thing, blacks are welcome down there now!’‘ -- in Tatz, Colin (ed.) 1975, Black Viewpoints: The Aboriginal Experience,Sydney: Australian and New Zealand Book Company, pp. 35-6. Chicka was one of the central campaigners for the 1967 referendum, an active participant of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in the 1970s and a founder of the Aboriginal Legal Service and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). Chicka Dixon provided a key link between the earlier generations of working-class Indigenous activists and the post-1967 young ``Black Power" Indigenous activists. These young firebrands’ first stop in Sydney was the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs, an organisation with a social and cultural focus, which ``grew out of’‘ the Aboriginal Australian Fellowship (Barani Indigenous History of Sydney City 2002, ``Aboriginal Organisations in Sydney’‘). According to Chicka Dixon, the Foundation, as it was known, came into being 1964 and ``grew out of a discussion between myself, a fellow called Charles Perkins and Professor Bill Geddes of the Anthropology Department, Sydney University. We felt that black people in Sydney needed a centre where they could get advice about jobs, meals, places where they could have social activities, legal advice if necessary... Our general policy was to help Aborigines to help themselves... We would hold a Saturday dance night and a Sunday night concert’‘ (in Tatz 1975, pp. 36-7). At the Foundation, the new activists mixed with the older generation of militant leaders, such as Chicka Dixon and Ken Brindle. They `came to sense themselves as the inheritors of a long tradition of political struggle as they met and conversed with aging legends of the indigenous struggle such as Bill Onus, Jack Patten, Bert Groves’‘ (Foley 2001). On January 25, 1972, Liberal PM Billy McMahon announced that his government would not grant land rights. In response, young Indigenous radicals from Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane planned, established and ran the most famous of all Aboriginal protests, the long-running Aboriginal Tent embassy. Gary Foley described the origins of the protest: ``Indigenous leaders meeting in Sydney that night were outraged at what they regarded as stonewalling. By that time the core of the Redfern group comprised of Paul Coe and sister Isobel from Cowra, brilliant Qld writer and theorist John Newfong, Bob, Kaye and Sol Bellear, Tony Coorie from Lismore, Alana and Samantha Doolan from Townsville, Gary Wiliams and Gary Foley from Nambucca, Lyn Craigie and her brother Billy from Moree... One of the group’s mentors, Chicka Dixon, was keen on replicating the Native American's takeover of Alcatraz. He urged that they take over Pinchgut Island (Fort Denison) in Sydney harbour. `Not just take it over, defend it!’, he said, because when the Indians had taken over Alcatraz they had placed their peoples plight into `the eyes of the world’." In the end it was decided to go to Canberra and establish the Tent Embassy. Under the Whitlam government, Chicka was sent to Canada to study, employed alongside Charles Perkins in the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, established by Whitlam in 1973. Hawke appointed him chair of the Aboriginal Arts Board in 1983. The following year he was made Aboriginal of the Year.He is survived by his two daughters, Rhonda and Christine, and a large extended family.

[Based on information from http://www.labor.net.au/news/1269249966_3698.html, | ||||